by Stephen J. Gertz

"Ours are only more sophisticated, in better taste, more literate and civilized. In my 'Art of Pornography' I have hazarded a tentative definition of the genre, in so far as it can be considered a branch of literary art, as 'that kind of aphrodisiac writing which, no matter to what sexual disposition of vagary it is addressed, can command the interest of a judicious reader of dissimilar psychosexual disposition.' This rules out all kinds of trash but leans heavily on imponderables. I was simply trying to formulate some definition, to isolate what we know is good pornography (Cleland, Nerciat, Voisenon, Beardsley, Swinburne) from the mass of rubbish like Rosa Fielding, The Lustful Turk, etc. and such dead horses as poor Steven Marcus flogs so pointlessly [in The Other Victorians]. I was subjecting pornography to an aesthetic test: perhaps thereby imposing on it a dead critical hand. - the essential mystery of sadomasochism itself remains dark, and I for one shall never unravel it. All I know is that like all forms of psychosexuality it is auto-erotic, subjective, and the partner sought (and sometimes found, and isn't this a blessing) in real life is only a projection of one's own self. One does find one's alter-ego, as I know; and so does she, and then everything in the garden is lovely, even for years. The real Luv arrives, and dulls the sharp end of sex, and both go wandering off on their endless quest for variety, separately alas, still seeking some new double version of the self..."

"Dear old Bizarre! It was an oasis back in the dreary fifties. Yes, I remember the wonderful photo of of Mlle Polaris, the Queen of the Wasp-waists, in her extraordinary corset, which John Willie unearthed and reprinted….He was a Pioneer. Though his pony-girl fantasy, in monthly episodes, did get rather tedious: the writing was so amateur…

"Thanks for your suggestion that I send the Governess to the Penthouse Book Society. Alas, I sold all British rights outright, in dear Harriet to one Aaron M. Shapiro of New York for $1,000 down and 50% of everything he can get over this. And notre cher Maurice G. owns the rights to the obscene version. He still owes me $500 (due last July) but what hope. So I am now only an onlooker of the progress of this absurd book. It gives me unexampled delight to see it on drugstore counters and being bought by liplicking trembly-handed gents on Montreal. These are the true rewards of authorship" (Sept 3, 1968).

On April 12, 1970, copies of Glassco's Temple of Pederasty sent to him by the publisher in California were intercepted at the Canadian border, examined in Ottawa, and determined to be "immoral or indecent." On April 24th, Glassco wrote Wagner:

"I just might make an issue of this. I am consulting our great F.R. Scott (Lady Chatterley's Lawyer) about this next week. After all, these 18 free copies are mine by right, aren't they? I'm mad as hell about this virtual confiscation of my proputty."

On June 16, 1971, Glassco wrote Wagner:

"Thank you so much for Gynecocracy [1893] and The Boudoir [1880s magazine]: they are both banned in this moral province [Quebec]. These Victorian things have always had a great appeal to me, largely as period pieces. In spite of or perhaps because of their awkwardness, bad grammar and super-abundance of cliché (descriptively, the girls simply don't exist!), they are still readable and often stimulating. What I find their greatest fault is their lack of verisimilitude, the demands they make on the reader for an utter suspension of common sense, and a certain monotony. But what is most interesting is that their very situations, action and preoccupations are still being reproduced in places like the correspondence column of Justice Weekly: in porno, there is almost nothing new under the sun! - Well, these old books were of course for the most part carelessly and hastily written: Gynecocracy begins rather well but falls down badly about half-way through, with absurdity piled on absurdity as the author either became tired or lost all sense of proportion. I think you and I have done much better in the genre; the next generation will be reading us, rather than them, I'm sure…Even at that, however, I think we tend to bypass reality rather too much: it's such a temptation to let one's fancy lightly fly! And to pile things on. At least it is so in my case:I've forgotten Horace's ne nimium advice much too often.

"But this raises the whole question of an aesthetic of pornography, the matter of raising it to the plane of art, as Cleland and Nerciat somehow did. Perhaps we should try and forget the Victorians: they are, subtly, too much with us, too sweetly oppresive by reason of their décor, richness and nostalgia. But what milieu, what locus, can take their place? Our art is essentially romantic, and seeks a never-never climate; yet it must, I think, take more account of reality than it has in the past. This means, to begin with, it must have a strong story-line, a good skeleton as it were; it should also be psychologically viable; and should even have a certain moral truth such as it had in the 18th century. Perhaps this involves giving our work a wry, tragic, or unhappy ending. Quite a programme, indeed!"

It remains a mystery just who John Glassco really was. For all the light Mr. Busby has diligently shone on the man, and no matter how revealing his letters, John Glassco remains, however open, charming and generous of spirit - his heart, indeed, accepted it all - something of a puzzle, he seemed to prefer it that way, and he's all the more fascinating because of it. He enjoyed pseudonymity and creating a tall-tale context for his erotica. His pleasure was writer as actor portraying his characters. He was one of Canada's gifts to literature, a gentleman litterateur in a smoking jacket with a talent for literary sex.

Scraping the crumbling roadbed of this strife

With rotting fenceposts and old mortgages

(No way of living, but a mode of life),

How sift from death and waste three grains of duty,

O thoughts that start from scratch and end in a dream

Of graveyards minding their own business?

But the heart accepts it all, this honest air

Lapped in green valleys where accidents will happen!

— John Glassco, "The Rural Mail"

With rotting fenceposts and old mortgages

(No way of living, but a mode of life),

How sift from death and waste three grains of duty,

O thoughts that start from scratch and end in a dream

Of graveyards minding their own business?

But the heart accepts it all, this honest air

Lapped in green valleys where accidents will happen!

— John Glassco, "The Rural Mail"

What distinguishes good porn from bad? Is there an aesthetic of pornography? Are porn novels an essentially romantic genre of literature? What are the true rewards of authorship? Is Margaret Atwood a sexual fetishist? And did Leonard Cohen really want to give up singing and join the Israeli army?

Last year, A Gentleman of Pleasure, literary historian Brian Busby's biography of the enigmatic Canadian poet, memoirist, acclaimed translator of French-Canadian poetry, novelist, pornographer, and literary hoaxster, John Glassco, the self-proclaimed "great practitioner of deceit," was published. Now, Mr. Busby presents The Heart Accepts It All, a selection of Glassco's letters.

Glassco's correspondents included novelist Kay Boyle; poet and novelist, Robert McAlmon; Olympia Press publisher Maurice Girodias; novelist, poet, and critic Malcolm Cowley; novelist Margaret Atwood; Henry James' biographer, Leon Edel; and many other literary notables, including novelist, literary and cultural critic, and professor, Geoffrey Wagner, who, under the pseudonym, P.N. Dedeaux, wrote a handful of erotic novels in the 1960s and early '70s that remain amongst the best written of the era.

|

| DEDEAUX, P.N. [Geoffrey Wagner]. Tender Buns. North Hollywood: Essex House #0126, 1969. First edition. |

Glassco, whose Memoirs of Montparnasse (1970) is considered to be the best view of expatriate Paris in the 1920s, had a gift for stylistic imitation. He seamlessly completed Aubrey Beardsley's unfinished erotic novel, Under the Hill (aka Venus and Tannhauser) for Olympia Press in Paris (1959). He wrote the erotic poem, Squire Hardman, which he mischievously ascribed to George Colman the Younger, a once popular British dramatist and writer of the late eighteenth- early nineteenth centuries).

He was the author of what is arguably the best-selling, most popular erotic novel in English of all time, The English Governess by Miles Underwood (Paris: Ophelia Press [Olympia Press], 1960) aka Harriet Marwood, Governess, The Authentic Confessions of Harriet Marwood, An English Governess; The Governess; Under the Birch, and who knows how many other reprint titles, a novel so often pirated that it may hold a record in that department, too. Glassco also wrote Fetish Girl by Sylvia Bayer, which he, with a gallant wink, dedicated, "To John Glassco."

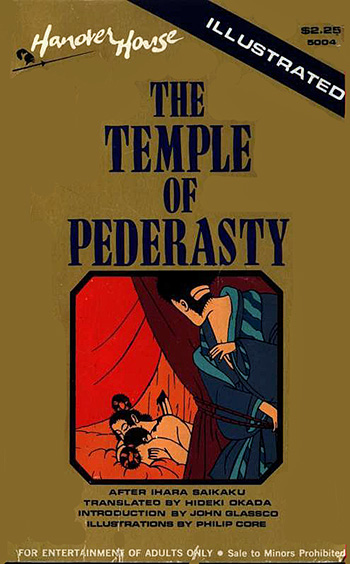

He wrote the Introduction to The Temple of Pederasty by Ihara Saikaku, translated by Hideki Okada (Brandon House/Hanover House, 1970). He wrote more than the Introduction. The book, purportedly based on one by the very real 17th century Japanese poet and novelist, Ihara Saikaku (1642-93), the volume is an grand exercise in literary deception. The translator, 'the late Dr. Hideki Okada,' is actually Glassco himself. Glassco's translation (in his word, "interpolation") is, for the most part, derived from Ken Sato's unintentionally hysterical and inept translation of Saikaku's Quaint Stories of the Samurais, a collection of homoerotic tales published by Robert McAlmon, Paris, 1928.

|

| First edition. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1970. |

He was the author of what is arguably the best-selling, most popular erotic novel in English of all time, The English Governess by Miles Underwood (Paris: Ophelia Press [Olympia Press], 1960) aka Harriet Marwood, Governess, The Authentic Confessions of Harriet Marwood, An English Governess; The Governess; Under the Birch, and who knows how many other reprint titles, a novel so often pirated that it may hold a record in that department, too. Glassco also wrote Fetish Girl by Sylvia Bayer, which he, with a gallant wink, dedicated, "To John Glassco."

He wrote the Introduction to The Temple of Pederasty by Ihara Saikaku, translated by Hideki Okada (Brandon House/Hanover House, 1970). He wrote more than the Introduction. The book, purportedly based on one by the very real 17th century Japanese poet and novelist, Ihara Saikaku (1642-93), the volume is an grand exercise in literary deception. The translator, 'the late Dr. Hideki Okada,' is actually Glassco himself. Glassco's translation (in his word, "interpolation") is, for the most part, derived from Ken Sato's unintentionally hysterical and inept translation of Saikaku's Quaint Stories of the Samurais, a collection of homoerotic tales published by Robert McAlmon, Paris, 1928.

In Glassco's letters to Wagner he shares his thoughts on literary pornography.

"Ours are only more sophisticated, in better taste, more literate and civilized. In my 'Art of Pornography' I have hazarded a tentative definition of the genre, in so far as it can be considered a branch of literary art, as 'that kind of aphrodisiac writing which, no matter to what sexual disposition of vagary it is addressed, can command the interest of a judicious reader of dissimilar psychosexual disposition.' This rules out all kinds of trash but leans heavily on imponderables. I was simply trying to formulate some definition, to isolate what we know is good pornography (Cleland, Nerciat, Voisenon, Beardsley, Swinburne) from the mass of rubbish like Rosa Fielding, The Lustful Turk, etc. and such dead horses as poor Steven Marcus flogs so pointlessly [in The Other Victorians]. I was subjecting pornography to an aesthetic test: perhaps thereby imposing on it a dead critical hand. - the essential mystery of sadomasochism itself remains dark, and I for one shall never unravel it. All I know is that like all forms of psychosexuality it is auto-erotic, subjective, and the partner sought (and sometimes found, and isn't this a blessing) in real life is only a projection of one's own self. One does find one's alter-ego, as I know; and so does she, and then everything in the garden is lovely, even for years. The real Luv arrives, and dulls the sharp end of sex, and both go wandering off on their endless quest for variety, separately alas, still seeking some new double version of the self..."

"Dear old Bizarre! It was an oasis back in the dreary fifties. Yes, I remember the wonderful photo of of Mlle Polaris, the Queen of the Wasp-waists, in her extraordinary corset, which John Willie unearthed and reprinted….He was a Pioneer. Though his pony-girl fantasy, in monthly episodes, did get rather tedious: the writing was so amateur…

"Thanks for your suggestion that I send the Governess to the Penthouse Book Society. Alas, I sold all British rights outright, in dear Harriet to one Aaron M. Shapiro of New York for $1,000 down and 50% of everything he can get over this. And notre cher Maurice G. owns the rights to the obscene version. He still owes me $500 (due last July) but what hope. So I am now only an onlooker of the progress of this absurd book. It gives me unexampled delight to see it on drugstore counters and being bought by liplicking trembly-handed gents on Montreal. These are the true rewards of authorship" (Sept 3, 1968).

|

| North Hollywood: Hanover House (Brandon House), 1970. |

"I just might make an issue of this. I am consulting our great F.R. Scott (Lady Chatterley's Lawyer) about this next week. After all, these 18 free copies are mine by right, aren't they? I'm mad as hell about this virtual confiscation of my proputty."

On June 16, 1971, Glassco wrote Wagner:

"Thank you so much for Gynecocracy [1893] and The Boudoir [1880s magazine]: they are both banned in this moral province [Quebec]. These Victorian things have always had a great appeal to me, largely as period pieces. In spite of or perhaps because of their awkwardness, bad grammar and super-abundance of cliché (descriptively, the girls simply don't exist!), they are still readable and often stimulating. What I find their greatest fault is their lack of verisimilitude, the demands they make on the reader for an utter suspension of common sense, and a certain monotony. But what is most interesting is that their very situations, action and preoccupations are still being reproduced in places like the correspondence column of Justice Weekly: in porno, there is almost nothing new under the sun! - Well, these old books were of course for the most part carelessly and hastily written: Gynecocracy begins rather well but falls down badly about half-way through, with absurdity piled on absurdity as the author either became tired or lost all sense of proportion. I think you and I have done much better in the genre; the next generation will be reading us, rather than them, I'm sure…Even at that, however, I think we tend to bypass reality rather too much: it's such a temptation to let one's fancy lightly fly! And to pile things on. At least it is so in my case:I've forgotten Horace's ne nimium advice much too often.

"But this raises the whole question of an aesthetic of pornography, the matter of raising it to the plane of art, as Cleland and Nerciat somehow did. Perhaps we should try and forget the Victorians: they are, subtly, too much with us, too sweetly oppresive by reason of their décor, richness and nostalgia. But what milieu, what locus, can take their place? Our art is essentially romantic, and seeks a never-never climate; yet it must, I think, take more account of reality than it has in the past. This means, to begin with, it must have a strong story-line, a good skeleton as it were; it should also be psychologically viable; and should even have a certain moral truth such as it had in the 18th century. Perhaps this involves giving our work a wry, tragic, or unhappy ending. Quite a programme, indeed!"

For all his genius as an editor-publisher, Maurice Girodias was a poor businessman with a casual attitude about contracts and author payments. Everyone who wrote for Maurice Girodias had complaints and Glassco was no exception.

On September 26, 1966 Glassco sent Girodias a postal spear with firm point.

"It has…come to my notice that you have published a book called Under the Birch, using the text of The English Governess, and are apparently selling it in various countries. This is a breach on copyright, since under our agreement of 30 March 1960, you had only the right to reprint The English Governess on payment to me of NF 3000 for each reprint. The new title means a new publication, not a reprint…

"In view of the difficulties I have experienced in the past in ensuring performance of our agreement of 30 March 1960 I am sure you will understand my insistence on payment of the $1000 in Canadian funds within three months of the date of this letter…"

On May 11, 1967, Glassco wrote Girodias again, his spear inspired by Nabokov's Lolita.

"Dear Maurice (if I may):

"I have just been reading your 'Sad Ungraceful Tale of Lolita' in the reprinted Olympia Reader, and was struck by the undoubted fact that Lolita would not, as you point out, heve been published at all; but for you: at which point I realized that this also holds true for Under the Hill, and that my last letter to you was written in an unduly heated state of mind…

"…There is a chance I may be sent to Paris on a government cultural mission in a week or so…I hope then to have the pleasure of calling on you, and talking on all subjects except that of money.

"Yours with kindest regards, John G."

Later in that year, Glassco wrote again to Girodias in response to a request (and Girodias' plan to reprint The English Governess in the U.S. under his Olympia Press- NY imprint). The request remains intriguing:

"Some new Sade translations might be within my powers this winter. My versions would be quite unlike [Austryn] Wainhouse's as to constitute original translation…Sade has a good clear rhetorical style, a little turgid, but full of a life and vivacity which do redeem the dryness and tedium of his philosophical ideas…All the English versions of Sade I've ever seen are quite unworthy of this inspired madman who surpasses St. Francis of Assisi in the scope of his ideas. Sade is the moral Columbus of our epoch."

Margaret Atwood interested in fetishism? Leonard Cohen in the Israeli army?

"June 16, 1971

"Dear Peggy

Thank you so much for The Undergrowth of Literature [by Gillian Freeman, 1967, a survey of sexual fantasy in literature]. I was specially struck by the chapter on rubber fetishism, which I can see is rampant over there [in England]. As a latex fan since the age of 4 (my true Venus has always worn a frogman's suit), I enjoyed it enormously. Also, I had just finished a short novel [Fetish Girl] whose characters wallow delicate in this fetish, and it was encouraging to read about its popularity in the U.K…

"…Leonard Cohen tells me he is finished with Literature and chansonnerie and suggests we both join the Israeli army…"

On September 26, 1966 Glassco sent Girodias a postal spear with firm point.

"It has…come to my notice that you have published a book called Under the Birch, using the text of The English Governess, and are apparently selling it in various countries. This is a breach on copyright, since under our agreement of 30 March 1960, you had only the right to reprint The English Governess on payment to me of NF 3000 for each reprint. The new title means a new publication, not a reprint…

"In view of the difficulties I have experienced in the past in ensuring performance of our agreement of 30 March 1960 I am sure you will understand my insistence on payment of the $1000 in Canadian funds within three months of the date of this letter…"

On May 11, 1967, Glassco wrote Girodias again, his spear inspired by Nabokov's Lolita.

"Dear Maurice (if I may):

"I have just been reading your 'Sad Ungraceful Tale of Lolita' in the reprinted Olympia Reader, and was struck by the undoubted fact that Lolita would not, as you point out, heve been published at all; but for you: at which point I realized that this also holds true for Under the Hill, and that my last letter to you was written in an unduly heated state of mind…

"…There is a chance I may be sent to Paris on a government cultural mission in a week or so…I hope then to have the pleasure of calling on you, and talking on all subjects except that of money.

"Yours with kindest regards, John G."

Later in that year, Glassco wrote again to Girodias in response to a request (and Girodias' plan to reprint The English Governess in the U.S. under his Olympia Press- NY imprint). The request remains intriguing:

"Some new Sade translations might be within my powers this winter. My versions would be quite unlike [Austryn] Wainhouse's as to constitute original translation…Sade has a good clear rhetorical style, a little turgid, but full of a life and vivacity which do redeem the dryness and tedium of his philosophical ideas…All the English versions of Sade I've ever seen are quite unworthy of this inspired madman who surpasses St. Francis of Assisi in the scope of his ideas. Sade is the moral Columbus of our epoch."

Margaret Atwood interested in fetishism? Leonard Cohen in the Israeli army?

"June 16, 1971

"Dear Peggy

Thank you so much for The Undergrowth of Literature [by Gillian Freeman, 1967, a survey of sexual fantasy in literature]. I was specially struck by the chapter on rubber fetishism, which I can see is rampant over there [in England]. As a latex fan since the age of 4 (my true Venus has always worn a frogman's suit), I enjoyed it enormously. Also, I had just finished a short novel [Fetish Girl] whose characters wallow delicate in this fetish, and it was encouraging to read about its popularity in the U.K…

"…Leonard Cohen tells me he is finished with Literature and chansonnerie and suggests we both join the Israeli army…"

|

| NY: Venus Library, 1972. First edition. |

In 1971 Glasco submitted the first chapter of Fetish Girl to Fraser Sutherland, publisher of Northern Journey, a Canadian literary journal, for publication.

"You may find FG disappointing. But don't forget that this is formula commercial pop-porno, beginning mildly because the action must always be a constant crescendo and all subsequent chapters depend closely on each other, and they can't be isolated. - By the way, FG is the first rubber-fetish novel ever written. [N.B. It was not. That honor lies with Rubber Goddess by Lana Preston (Paul Hugo Little, 1967).

"If you take this chapter - and please feel free to reject it in spite of your kind sight-uneen acceptance! - it must appear under the name of its true author Miss Sylvia Bayer, as the entire book will; nor should any reference be made to its publication this fall by Grove Press [under its Venus Library imprint], since this may invalidate her contract.

"I will send you a recent glossy of myself, and one of Miss Bayer, too…"

"To The Editors Of Northern Journey, July 15, 1971.

Dear Sirs: -

My good friend John Glassco has just told me you have accepted the first chapter of my latest novel Fetish Girl and I am delighted.

I understand you would like to use a photograph and to print some kind of introductory-biographical note.

I enclose the photograph. As for the note here also is a suggested first person text giving all relevant information and you can 3rd-person alter, cut, telescope or rearrange as you see fit. Only I must see the final text of whatever note you mean to use, I'm sorry to put you to this extra trouble, but I have to do it.

Yours sincerely,

Mrs. Sylvia Fenwick-Owen, 1224 Bishop St.,

Montreal 107

P.Q.

P.S. May I beg you to keep my home address quite confidential. Thank you."

"You may find FG disappointing. But don't forget that this is formula commercial pop-porno, beginning mildly because the action must always be a constant crescendo and all subsequent chapters depend closely on each other, and they can't be isolated. - By the way, FG is the first rubber-fetish novel ever written. [N.B. It was not. That honor lies with Rubber Goddess by Lana Preston (Paul Hugo Little, 1967).

"If you take this chapter - and please feel free to reject it in spite of your kind sight-uneen acceptance! - it must appear under the name of its true author Miss Sylvia Bayer, as the entire book will; nor should any reference be made to its publication this fall by Grove Press [under its Venus Library imprint], since this may invalidate her contract.

"I will send you a recent glossy of myself, and one of Miss Bayer, too…"

"To The Editors Of Northern Journey, July 15, 1971.

Dear Sirs: -

My good friend John Glassco has just told me you have accepted the first chapter of my latest novel Fetish Girl and I am delighted.

I understand you would like to use a photograph and to print some kind of introductory-biographical note.

I enclose the photograph. As for the note here also is a suggested first person text giving all relevant information and you can 3rd-person alter, cut, telescope or rearrange as you see fit. Only I must see the final text of whatever note you mean to use, I'm sorry to put you to this extra trouble, but I have to do it.

Yours sincerely,

Mrs. Sylvia Fenwick-Owen, 1224 Bishop St.,

Montreal 107

P.Q.

P.S. May I beg you to keep my home address quite confidential. Thank you."

Whose photograph did Glassco submit as that of "Sylvia Bayer?" His first wife, Elma. Fraser Sutherland had no idea. Glassco's friends did and were startled.

It remains a mystery just who John Glassco really was. For all the light Mr. Busby has diligently shone on the man, and no matter how revealing his letters, John Glassco remains, however open, charming and generous of spirit - his heart, indeed, accepted it all - something of a puzzle, he seemed to prefer it that way, and he's all the more fascinating because of it. He enjoyed pseudonymity and creating a tall-tale context for his erotica. His pleasure was writer as actor portraying his characters. He was one of Canada's gifts to literature, a gentleman litterateur in a smoking jacket with a talent for literary sex.

__________

Full disclosure: Mr. Busby is a friend, and in the book generously acknowledges the meager assistance I provided by answering a few questions.

__________

__________

_13.jpg)